In general, outlook on urethral stricture is favorable. Depending on the underlying cause, some cases may carry a poorer prognosis.

Home » Urethral Stricture

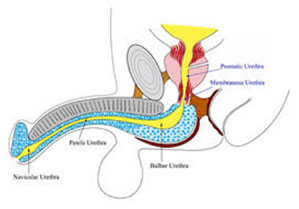

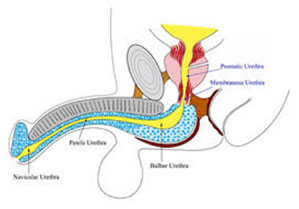

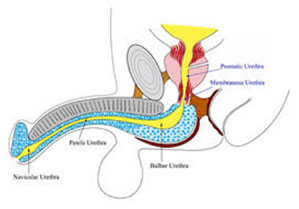

In men, the urethra is a thin tube like structure that starts from the lower opening of the bladder and traverses the entire length of the penis. The urethra has a sphincter that is normally closed to keep urine inside the bladder. When bladder fills with urine, there are both voluntary and involuntary controls to open the urethral sphincter to allow urine to come out.

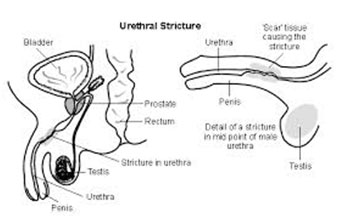

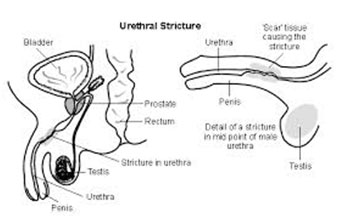

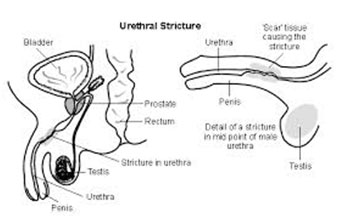

Urethral stricture refers to any narrowing of the urethra for any reason whether or not it actually impacts the flow of urine out of the bladder. Any inflammation of urethra can result in scarring, which then can lead to a stricture or a narrowing of the urethra. Trauma, infection, tumors, surgeries, or any other cause of scarring may lead to urethral narrowing or stricture.

Mechanical narrowing of the urethra without scar formation (developmental causes or prostate enlargement) can also cause urethral stricture.

The following are common causes of scarring or narrowing of the urethra:

About one-half of causes of urethral stricture are from medical procedures and manipulation of the urethra or nearby structures (surgeries, catheter insertion, etc.). In about one-third of cases, no identifiable cause are found.

Symptoms of urethral stricture can range from no symptoms at all (asymptomatic), to mild discomfort, to complete urinary retention (inability to urinate).

Some of the possible symptoms and complications of urethral stricture include the following:

When the medical history, physical examination, and symptoms are suggestive of urethral stricture, additional diagnostic tests may be helpful in further evaluation. Urinalysis (UA), urine culture, and urethral culture for sexually transmitted diseases (gonorrhea, chlamydia) are some of the typical tests that may be ordered in this setting. Oftentimes, imaging and endoscopic studies are necessary to confirm the diagnosis and identify the cause of urethral strictures.

The following are some common imaging and endoscopic tests in evaluating urethral stricture:

Ultrasound of the urethra is one of the radiologic methods in evaluating urethral stricture. An ultrasound probe can placed along the length of the penis (phallus) and determine the size of the stricture, degree of narrowing, and length of the stricture. This is a non-invasive method and usually does not require any special preparation.

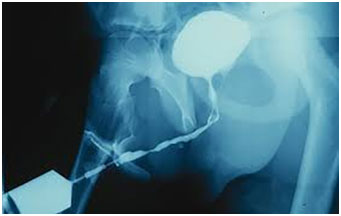

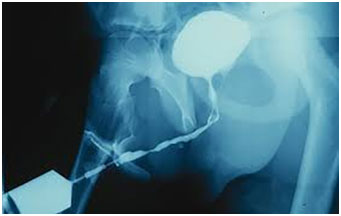

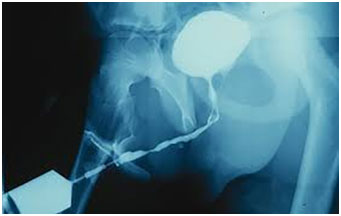

Retrograde urethrogram (RGU) is another radiology test to evaluate urethral strictures. This test basically entails placing a small urinary catheter in the last part of the urethra (closest to the tip of the penis). Approximately 10 cc of an iodine contrast material is slowly injected in the urethra via the catheter. Then, radiographic pictures are taken under fluoroscopy to assess any obstruction or impairment to the flow of the contrast material that can suggest urethral stricture. This test provides useful information about the location, extent, and size of any narrowing in the urethra as well as the shape of any possible abnormalities.

Anterograde cystourethrogram is a similar test but can only be done if there is a suprapubic catheter in place (a urinary catheter placed in the bladder through the skin in the lower abdomen). Iodine contrast is then injected into the bladder via the catheter and its flow out of the urethra is radiographed under fluoroscopy.

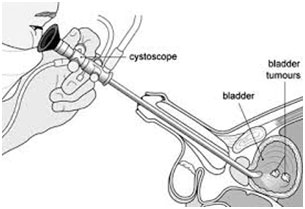

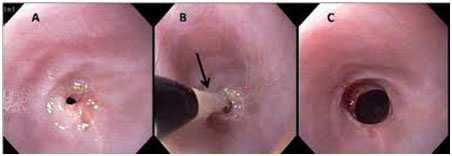

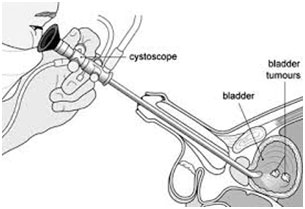

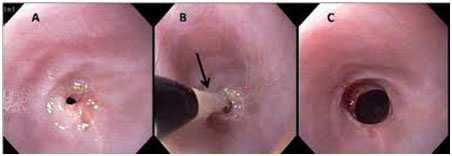

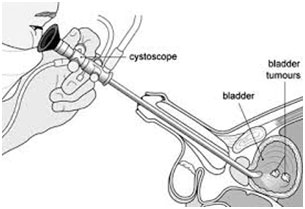

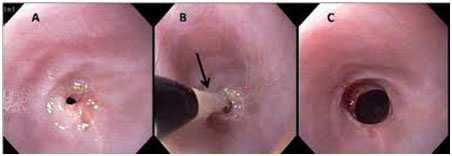

Cystourethroscopy is an endoscopic evaluation in which a small camera at the tip of a thin tube is inserted into the urethra for direct visualization of the lumen of the urethra. The tip of the urethral opening is cleansed, and local lubricant and anesthetic gels are applied for comfort. Then the endoscope is inserted into the urethra and bladder. Any anatomical or structural abnormalities will be detected, and a biopsy can be obtained at the same time if necessary.

There are essentially no real medical treatments (medications) for urethral strictures other than those offering symptom control (for example, pain medications to control discomfort). Surgery remains the only treatment for individuals with uncontrolled symptoms of urethral narrowing.

Surgery may be recommended in the following circumstances:

Many surgical procedures are available for treating urethral strictures. Depending on the cause and other medical and social aspects, the most appropriate procedure may be recommended for each individual case. The common procedures include

Urethral dilation is a commonly attempted technique for treating urethral strictures. This procedure is done under local or general anesthesia. Thin rods of increasing diameters are gently inserted into the urethra from the tip of the penis (meatus) in order to open up the urethral narrowing without causing any further injury to the urethra. This procedure may need to be repeated from time to time, as strictures may recur. The shorter the stricture, the less likely it is to recur after a dilation procedure. Occasionally, patients are given instructions and dilation instruments (rods, lubricating gel, and anesthetic gel) to perform the urethral dilation at home as needed.

Optical internal urethrostomy is an endoscopic procedure that is typically done under general anesthesia. A thin tube with a camera (endoscope) is inserted into the urethra to visualize the stricture (as describe in earlier section). Then a tiny knife is passed through the endoscope to cut the stricture lengthwise and open the flow of urine. A Foley catheter (urinary catheter) is then inserted and kept in place for a few days while the urethral incision is healing. The success rate of this procedure is about 25%, and again, shorter strictures generally have a better response to this procedure.

Urethral stent placement is another endoscopic procedure aimed at treating urethral strictures. Depending on the location of the stricture in the urethra, a closed tube (stent) can be passed through an endoscope to the area of the stricture. Once it reaches the proper location, then the stent can be opened to form a patent tube or conduit for urine to flow.

Open reconstruction entails several possible techniques for correction of urethral strictures. These are surgeries that involve opening the urethra surgically under general anesthesia to fix the stricture. In some, the area of scarring is cut out and the remaining urethra is reconnected. In others, after the scar tissue is removed, a graft from inside the cheek (buccal mucosa) or a skin flap may be used to form a reconstructed urethra. These techniques in general have a good response rate, although they are more invasive than other described procedures.

The treating urologist would recommend the procedure that would be the best option for each individual. As with any medical procedures, there is some degree of risks and complications associated with any of these operations.

In general terms, urethral stricture is not preventable as most common causes are related to injury, trauma, instrumentation, or unpreventable medical conditions. Sexually transmitted diseases such as gonorrhea or chlamydia are less common causes of urethral stricture, and they can be potentially prevented by practicing safe sex.

In general, outlook on urethral stricture is favorable. Depending on the underlying cause, some cases may carry a poorer prognosis.

मुत्र नलियों के मुत्र निकासी में अवरोध होने का कारण स्ट्रीक्चर हो सकता है यह बिमारी मुत्र नली में संक्रमण, चोट लगना या पुर्व में मुत्रनली

का कोई शल्य क्रिया होने के कारण होती है। यह बिमारी दवाईयों द्वारा ठीक नही होती है।

मुत्रनली पेशाब की थैली से मुत्र का निकास करने के लिये पुरूड्ढों में लिंग में स्थित होती है।मुत्राशय ;पेशाब की थैलीद्ध में सामान्तया युरिन भर

जाने के बाद मुत्राशय के सिरे पर स्थित वाल्व खुल जाते है जिससे कि मुत्र नली द्वारा मुत्र की निकासी सम्भव होती है, मुत्र निकासी के पश्चात

पेशाब की थैली के सिरे पर स्थित ये वाल्व पुनः बन्द हो जाते है जिससे कि मुत्राशय में पेशाब दुबारा इकटठा हो सके।

युरिथ्रल स्ट्रीक्चर मुत्र नली में सिकुडन अथवा अवरोध ;थ्पइतवेपेद्ध के कारण युरिन की निकासी कम हो जाती है या बन्द हो जाती है इस बिमारी

का कारण संक्रमण, पेशाब नली/ मुत्र नली का पुर्व में किया शल्य क्रिया, मुत्र नली में चोट लगना अथवा प्रोस्टेट के बढना के कारण उत्पन्न होती

है।

युरिन की जांच।

युरिन नली के अन्दर दवा डालते हुए (RGU) एवं मुत्र निकासी के समय (MCU) एक्स रे करना।

अल्ट्रासाउन्ड/एम.आर.आई. द्वारा जांच करना।

दुरबीन/सलाई द्वारा मुत्र नली की जांच करना।

मुत्र नली में सधन रूकावट न होने पर विशेड्ढ स्टील की नली (DILATOR) द्वारा लोकल एनेस्थिसिया अथवा सुक्ष्म जनरल एनेस्थिसिया मे नली

को चौड़ा किया जाता है।

दुरबिन विधि द्वारा नली की रूकावट सही करना।

बहुत छोटा एवं कम संधन (LESS THAN 1 cm) की रूकावटें दुरबिन विधि द्वारा मुत्र नली को सामान्य आकार में लाया जाता है।

बडें एवं लम्बे स्ट्रीक्चर में चीरे वाले आपरेशन की आवश्यकता पडती है जिसको स्पाइनल एनेस्थिसिया अथवा जनरल एनेस्थिसिया में किया जाता

है इसके अन्तर्गत 1 – 2.5 सेमी. की स्ट्रीक्चर को काटकर सामान्य हिस्सो का पुर्ण संयोजन किया जाता है। बडें अथवा मल्टीपल स्ट्रीक्चर मे

डाॅक्टर असोपा द्वारा विकसित विधि से उपचार किया जाता है इस विधि का प्रयोग दुनिया में लगभग सभी शल्य चिकित्सक करते है।

सामान्तया स्ट्रीक्चर युरिथ्रा सडक दुर्धटना, युरिथ्रा पर चोट लगने, शल्य क्रिया के दौरान साफ सुथरें औजार का प्रयोग न होना, लम्बें समय तक

पेशाब की नली पडें रहना एवं सैक्स के दौरान संक्रमण का आदान प्रदान होना उपरोक्त इन वजहो से भी स्टीक्चर युरिथ्रा हो जाता है।

Twitter feed is currently turned off. You may turn it on and set the API Keys and Tokens using Theme Options -> Social Options: Enable Twitter Feed.

In men, the urethra is a thin tube like structure that starts from the lower opening of the bladder and traverses the entire length of the penis. The urethra has a sphincter that is normally closed to keep urine inside the bladder. When bladder fills with urine, there are both voluntary and involuntary controls to open the urethral sphincter to allow urine to come out.

Urethral stricture refers to any narrowing of the urethra for any reason whether or not it actually impacts the flow of urine out of the bladder. Any inflammation of urethra can result in scarring, which then can lead to a stricture or a narrowing of the urethra. Trauma, infection, tumors, surgeries, or any other cause of scarring may lead to urethral narrowing or stricture. Mechanical narrowing of the urethra without scar formation (developmental causes or prostate enlargement) can also cause urethral stricture.

The following are common causes of scarring or narrowing of the urethra:

About one-half of causes of urethral stricture are from medical procedures and manipulation of the urethra or nearby structures (surgeries, catheter insertion, etc.). In about one-third of cases, no identifiable cause are found.

Symptoms of urethral stricture can range from no symptoms at all (asymptomatic), to mild discomfort, to complete urinary retention (inability to urinate).

Some of the possible symptoms and complications of urethral stricture include the following:

When the medical history, physical examination, and symptoms are suggestive of urethral stricture, additional diagnostic tests may be helpful in further evaluation. Urinalysis (UA), urine culture, and urethral culture for sexually transmitted diseases (gonorrhea, chlamydia) are some of the typical tests that may be ordered in this setting. Oftentimes, imaging and endoscopic studies are necessary to confirm the diagnosis and identify the cause of urethral strictures.

The following are some common imaging and endoscopic tests in evaluating urethral stricture:

Ultrasound of the urethra is one of the radiologic methods in evaluating urethral stricture. An ultrasound probe can placed along the length of the penis (phallus) and determine the size of the stricture, degree of narrowing, and length of the stricture. This is a non-invasive method and usually does not require any special preparation.

Retrograde urethrogram (RGU) is another radiology test to evaluate urethral strictures. This test basically entails placing a small urinary catheter in the last part of the urethra (closest to the tip of the penis). Approximately 10 cc of an iodine contrast material is slowly injected in the urethra via the catheter. Then, radiographic pictures are taken under fluoroscopy to assess any obstruction or impairment to the flow of the contrast material that can suggest urethral stricture. This test provides useful information about the location, extent, and size of any narrowing in the urethra as well as the shape of any possible abnormalities.

Anterograde cystourethrogram is a similar test but can only be done if there is a suprapubic catheter in place (a urinary catheter placed in the bladder through the skin in the lower abdomen). Iodine contrast is then injected into the bladder via the catheter and its flow out of the urethra is radiographed under fluoroscopy.

Cystourethroscopy is an endoscopic evaluation in which a small camera at the tip of a thin tube is inserted into the urethra for direct visualization of the lumen of the urethra. The tip of the urethral opening is cleansed, and local lubricant and anesthetic gels are applied for comfort. Then the endoscope is inserted into the urethra and bladder. Any anatomical or structural abnormalities will be detected, and a biopsy can be obtained at the same time if necessary.

There are essentially no real medical treatments (medications) for urethral strictures other than those offering symptom control (for example, pain medications to control discomfort). Surgery remains the only treatment for individuals with uncontrolled symptoms of urethral narrowing.

Surgery may be recommended in the following circumstances:

Many surgical procedures are available for treating urethral strictures. Depending on the cause and other medical and social aspects, the most appropriate procedure may be recommended for each individual case. The common procedures include

Urethral dilation is a commonly attempted technique for treating urethral strictures. This procedure is done under local or general anesthesia. Thin rods of increasing diameters are gently inserted into the urethra from the tip of the penis (meatus) in order to open up the urethral narrowing without causing any further injury to the urethra. This procedure may need to be repeated from time to time, as strictures may recur. The shorter the stricture, the less likely it is to recur after a dilation procedure. Occasionally, patients are given instructions and dilation instruments (rods, lubricating gel, and anesthetic gel) to perform the urethral dilation at home as needed.

Optical internal urethrostomy is an endoscopic procedure that is typically done under general anesthesia. A thin tube with a camera (endoscope) is inserted into the urethra to visualize the stricture (as describe in earlier section). Then a tiny knife is passed through the endoscope to cut the stricture lengthwise and open the flow of urine. A Foley catheter (urinary catheter) is then inserted and kept in place for a few days while the urethral incision is healing. The success rate of this procedure is about 25%, and again, shorter strictures generally have a better response to this procedure.

Urethral stent placement is another endoscopic procedure aimed at treating urethral strictures. Depending on the location of the stricture in the urethra, a closed tube (stent) can be passed through an endoscope to the area of the stricture. Once it reaches the proper location, then the stent can be opened to form a patent tube or conduit for urine to flow.

Open reconstruction entails several possible techniques for correction of urethral strictures. These are surgeries that involve opening the urethra surgically under general anesthesia to fix the stricture. In some, the area of scarring is cut out and the remaining urethra is reconnected. In others, after the scar tissue is removed, a graft from inside the cheek (buccal mucosa) or a skin flap may be used to form a reconstructed urethra. These techniques in general have a good response rate, although they are more invasive than other described procedures.

The treating urologist would recommend the procedure that would be the best option for each individual. As with any medical procedures, there is some degree of risks and complications associated with any of these operations.

In general terms, urethral stricture is not preventable as most common causes are related to injury, trauma, instrumentation, or unpreventable medical conditions. Sexually transmitted diseases such as gonorrhea or chlamydia are less common causes of urethral stricture, and they can be potentially prevented by practicing safe sex.

In general, outlook on urethral stricture is favorable. Depending on the underlying cause, some cases may carry a poorer prognosis.

Twitter feed is currently turned off. You may turn it on and set the API Keys and Tokens using Theme Options -> Social Options: Enable Twitter Feed.